Are you a Good Lake or a Bad Lake?

If North Dakota were a pan of brownies cut in nine pieces, Devils Lake would be the inside corner of the upper right-hand piece. It is a problematic place in several ways, beginning with its name. The Dakota tribe that lived here before the Europeans showed up called it “Spirit Lake”, but the whites morphed that into the much less poetic Devils Lake. That moniker fit better into their opinion of the Indians I suppose.

In addition to the name, the huge lake suffers from water quality problems. A thousand years ago the lake drained into the Sheyenne River, but not anymore. These days it acts as a drainage basin, rising and falling dramatically along with precipitation. Since there is no outlet to flush the lake, minerals are trapped and concentrated, giving Devils Lake the same problems with high salinity as the Salton Sea and the Great Salt Lake. The Corps of Engineers is trying to figure out how to “fix” the flooding and salt problems without making a worse mess somewhere else as they sometimes do. Fish and farmers may find the lake challenging, but waterfowl still think it’s a great place.

I had a blind reservation at Grahams Island State Park, located on an island in the middle of the big shallow lake, accessed by a five-mile causeway. This campground was very different from Turtle River in that the sites were all laid out in the open, parking lot fashion. What it lacked in scenery it made up for with very long spaces and full hookups, including sewer. Since I was planning on a short three-day stay this was fine.

The main attraction to the area other than the lake itself was Fort Totten, which was billed as post-Civil War cavalry outpost. The appeal was that the buildings were all original, not reconstructions, kind of an amazing thing for a fort built in 1867, so I wanted to check it out. I went in with a kind of John Wayne movie set expectation, but what I found there was something else completely.

Haunting Housing

Just like the nearby lake, Fort Totten is a bipolar place. There are two distinct stories here, each colored by the perspective of the teller. The official description from the State Historical Society of North Dakota is what you would expect from academia – a pasteurized accounting of facts from the conqueror’s viewpoint. This is the front end of the place, the Fort Apache type script from Hollywood, where intrepid cavalrymen bravely face Indians and elements that are equally hostile in the glory days of westward expansion.

description from the State Historical Society of North Dakota is what you would expect from academia – a pasteurized accounting of facts from the conqueror’s viewpoint. This is the front end of the place, the Fort Apache type script from Hollywood, where intrepid cavalrymen bravely face Indians and elements that are equally hostile in the glory days of westward expansion.

But even before you reach this marker, you get the feeling that something isn’t quite right. To get to Fort Totten, you must drive into the heart of the Spirit Lake Reservation, which encompasses the Southern shore of Devils Lake. The evidence of poverty in parts of the reservation is unmistakable. Although the historic site is sanctioned by the State, it is located in and run by, the Dakota people. To them, the story of Fort Totten is not a romantic tale of the West, it is the tragic story of a prison camp.

(To the credit of the Historical Society, they tell a more enlightened story these days then they did in 1975 when they made that plaque.)

There is a small but informative museum attached to the gift shop where you pay your entry fee, and then you are free to make your way around the square parade ground as you wish. Many of the buildings contain exhibits, a few have been remodeled for modern use. A couple of structures have been gutted and are in the process of stabilization and a few are boarded up and crumbling for lack of funding.

One of the more elaborate displays was the post store, fully stocked with period sundries. There were also soldier barracks exhibits and such from the days when Fort Totten was an active Army post.

One structure contained cases of dusty artifacts from fraternal organizations, notably the Oddfellows. Odd it was indeed, and the non sequitur added to my growing uneasy feeling about the place.

After the Army abandoned the Fort, the government gave the property over to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The BIA used the facility as one of their Indian Boarding Schools for the next forty years. In this program, the BIA forcibly removed children from their homes to “acculturate and assimilate” them into white society. These schools were funded by the government but run by private operators, pretty much the same way concessionaires now operate boat rentals and snack bars in the National Parks.

The BIA figured the best way to break the native people away from their savage ways was to give them a new religion, so they randomly assigned the boarding schools to a variety of Christian denominations. The Fort Totten Industrial School was assigned to the Grey Nuns of Montreal. Chippewa and Dakota children were made roommates, despite the fact that their tribes were longtime enemies. The Nuns spoke mainly French and did not understand either native language. They were supposed to teach these kids English. Our government is so wise.

Any student that was caught speaking their native tongue received draconian punishment from the Sisters. This sort of thing went on in one form or another until 1959 when the tribes were finally allowed to begin assuming control over their own schools.

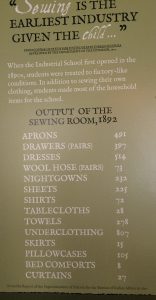

The “Industrial” part of the school’s mission was to teach students a trade so that they could become productive members of the mainstream population. While the school could claim some degree of success here, in practice it seems the children were used largely as free labor to support the school and the church. One interesting display quantified the output of the sewing operation for the year of 1892:

The structures themselves told a less depressing story. I can always find an appreciation in the craftsmanship and beauty in an old structure, no matter what its purpose .

Overall my experience at Fort Totten left me with a feeling of sadness. Historians who embellish the idea of America as “the Great Melting Pot” conveniently skip over the plight of people who never asked to be homogenized.

As I was driving back to the campground, I passed groups of young Dakota kids chasing about, riding bikes without helmets and splashing in the waters of Spirit Lake. At the edge of the reservation was a glitzy casino, with the parking lot full of shiny cars from the town of Devils Lake on the North shore. It lifted my spirits to see these people continue to find ways to survive and maintain a semblance of their culture despite a hundred-year effort by our government to wipe them out. As a side note, the Grey Nuns of Montreal ceased to exist as an organization in 2013. Their convent is now a Concordia University dormitory.

I think it is fitting that I close this post by giving the last word to the people of Spirit Lake Reservation. Dakota Prayer

A grim reminder of how we adjust history to justify our purposes. But I enjoy your reflections and your eye for for the way things were and how they were made.

What a wonderful prayer: “Teach us to walk the soft earth as relatives to all that live.”

You’re doing that now.